CAPITAL BUDGETING: LONG-RUN DECISION MAKING

This section discusses about the concepts and principles used by managers for their day to day investment related decision making.

1. NEED & BUSINESS SCENARIOS

An organization always expects a return on its investment. In case of capital investments or investments in long-lived assets; these returns are often in the form of additional cash inflows generated by using the assets. Therefore, whether or not to invest in a long-term asset depends on if it can generate additional cash-flows required to warrant its purchase.

There are several business scenarios where such cost benefit analysis is required to make an investment decision. Some of these business scenarios are discussed below –

- Cost reduction

Whether to invest in equipment for performing an operation which is otherwise done manually is one such scenario. The fundamental question here is that if this equipment can save significant cash outflows by lowering current operating costs.

- Replacement

Should we replace our existing equipment with new upgraded equipment? Upgraded equipment can benefit the organization either by reducing operating costs or by increasing production capacity; thus bringing in more earnings via revenues. The trade off in this case is between the savings plus incremental revenue from the upgraded equipment versus cost of installing it.

- New Product launch

Should an organization diversify into other products & services? The analysis here is in between whether the additional cash inflows generated by the launching new product or service is large enough to warrant the investment required for its production, marketing and other related costs.

- Expansion

Should we spend on expanding our current facilities to produce more volumes of products? Analysis required here would be whether profits from the goods produced would justify the investments required for expansion.

- Multiple proposals

Organizations often face situations where they are supposed to select one from several investment options. These options are compared and evaluated for their expected returns and the ones with the maximum returns are often selected.

Cash flows generated by long-lived assets are often expected & distributed over several years of its useful life while investment on them is required immediately. Thus, while evaluating benefits or return on these investments, it is necessary to bring all these cash flows to the same timeline. This brings us to the concepts of Present Value. Following section discusses these concepts in detail –

2. PRESENT VALUE

Present value concept is based on the principle that, “Money available today is worth more than an equivalent amount of it, that is expected in future”.

The concept is used widely by professionals for valuing liabilities and monetary assets. It is also used as a useful tool for evaluating proposals related to long term investments like purchase of a fixed assets etc.

For understanding present value concept, it is important to understand principles of compound interest & discounting.

2.1 COMPOUND INTEREST

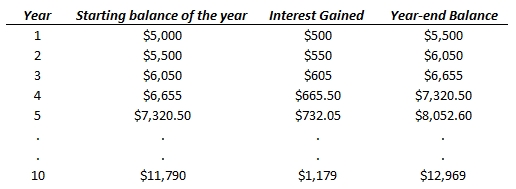

Example. Below, we illustrate a basic example depicting how compound interest works. Consider a person deposits $5,000 at a compound interest (annually) of 10% in his bank account. Assuming he made this investment for next 10 years, the balances on this account over period of investment are likely to be as follows –

Based on the table above, we can say that $5,000 invested today at 10% compound interest (annually) will give us a return of $12,969 in 10 years. In other words, this transaction is equivalent to saying that future value (FV) of $5,000 invested today at 10% interest for next 10 years is $12,969.

Instead of tracking growth year by year in tabular form (as shown above), we can use the below formula for obtaining values directly –

Where,

i = interest rate, p = principal amount (or, initial investment), n = number of periods

Thus, the future value (FV), of $5000 invested for 10 years at 10% compound interest is given by,

2.2 DISCOUNTING

The opposite of compounding concept is called discounting. In the above example, we calculated the future value (FV) of $5,000 invested for 10 years at 10% interest rate to be $12,969. The same statement can also be interpreted in terms of discounting as “present value of $12,969 discounted at 10% for 10 years would be $5,000”. The rate of interest in this context is called as discount rate. Some analysts also call this rate as hurdle rate or the required rate of return.